The Irene Sherman Project

Local Color

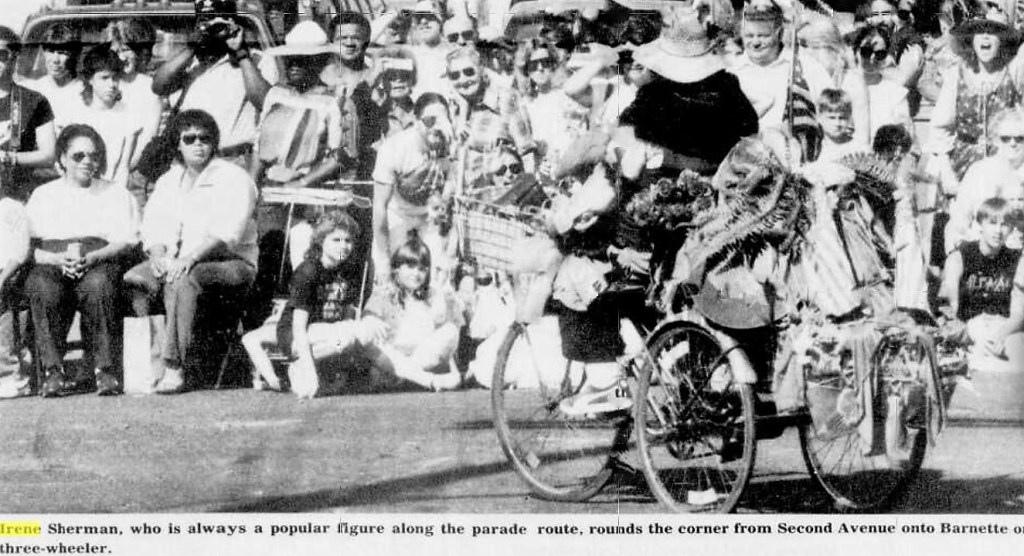

Around Fairbanks, Irene was a familiar sight–a terribly scarred woman in layers of tattered clothes who walked miles a day and loudly greeted friends with great warmth. Year after year she was both loved and feared, cussing like a sailor, drinking like a college kid, and hoarding her treasures at the junkyard she called home. Ask any long-timer. They’ll have an Irene story. She was uniquely Alaskan, uniquely Fairbanksan. She was watched over, invited in for meals, driven to appointments, and helped financially by pioneer families and newcomers alike, people who did not draw attention to their generosity. Irene was not just any bag lady. She was our bag lady.

Irene’s Early Life

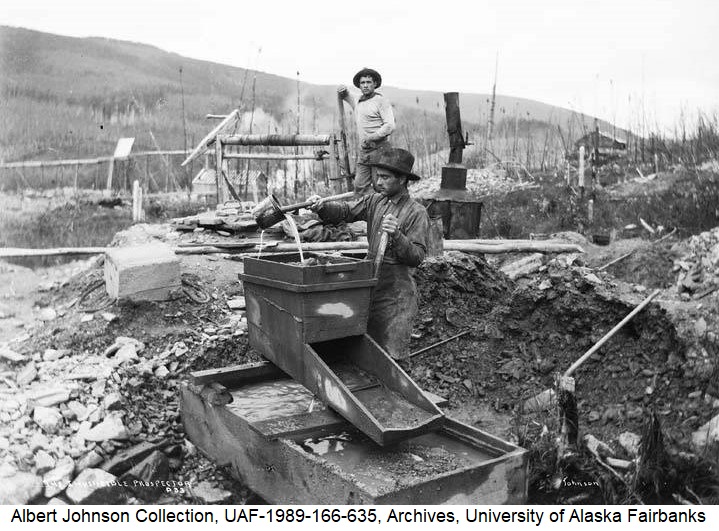

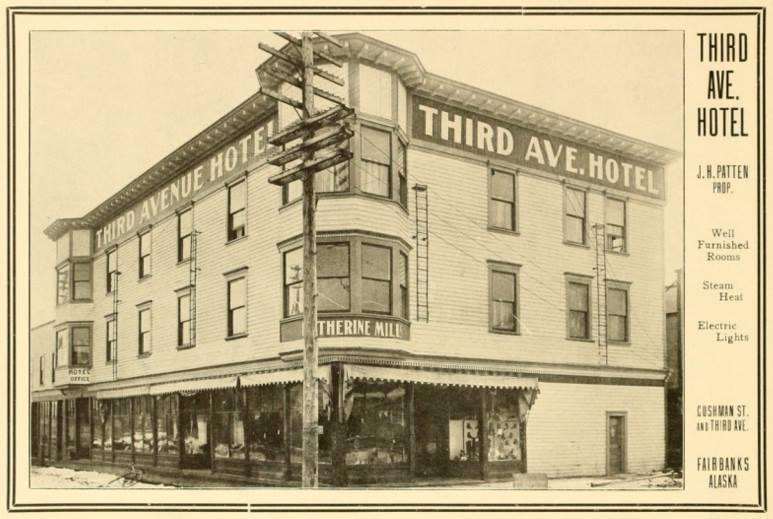

Irene Sherman’s roots in the Golden Heart City were deep. Her parents and maternal grandparents were among the earliest citizens of the young gold camp called Fairbanks. Grandmother Minnie Eckert had moved north from Seattle in 1905 after a divorce, and brought two teenaged children with her. One of them was Irene’s mother, Agnes Eckert. In 1908, Minnie remarried John Patten, who owned and operated the lavish Third Avenue Hotel along Cushman Street between Third and Fourth, and it was there in the hotel parlor that in 1910 daughter Agnes married James Paul (or J. P.) Sherman. He had stampeded to Fairbanks when news of gold discovery took off, but he chose to trap fur-bearing animals and mine for gold in the Bonnifield District, south of the Tanana River and north of the Alaska Range foothills.

And then at age five . . .

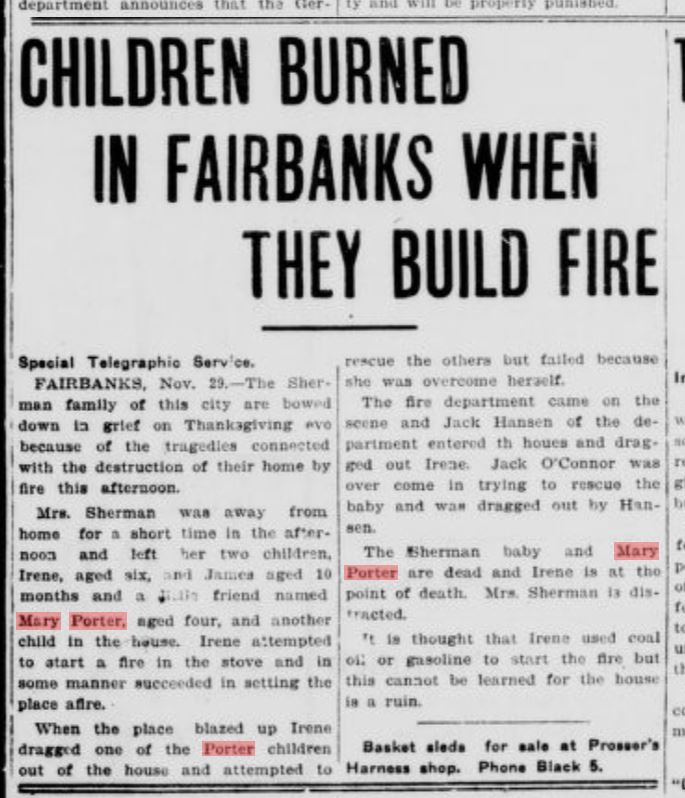

J. P. was out of town in the days before Thanksgiving 1916 when a raging cabin fire in Fairbanks nearly killed Irene and took the lives of her nine-month-old baby brother, James, and a neighbor girl named Mary Porter who’d come over to play. The children had been left alone while Irene’s mother Agnes went out socializing for the day. Irene alone survived, but would spend ten years in the Seattle area undergoing further medical treatment and bouncing among foster homes before landing in a convent school. She would not return to Alaska until 1929. The toll of her early childhood trauma was immeasurable.

Photo Gallery